Decentralisation of the electrical energy market and the role of prosumers

By Attilio Di Sabato

Production

Every country has large power plants that produce energy, most of which are privately owned and use non-renewable sources. The share of electricity that is not produced domestically is purchased and imported from abroad through international grid connections. For example, in 2019 domestic electricity production supplied 88.1% of demand, of which 60% comes from non-renewable thermoelectricity.1

Transmission

The Transmission System Operator (TSO) manages energy flows within the national grid by constantly balancing energy supply and demand, avoiding grid problems. The energy produced is fed into the grid via high voltage and then managed and dispatched by the TSO via storage systems and transformer stations. In Italy, Terna Group is the TSO and manages approximately 74,669 km of the grid.

Distribution

Unlike the TSO, which often has a public monopoly, Distribution System Operators (DSOs) can be private and more than one. In fact, there are currently around 127 in Italy. DSOs are responsible for distributing energy and operate the primary (HV/MV) and secondary (MV/LV) substations, as well as the final low voltage (LV) portion of the electricity grid under concession. In this way, energy from the other transmission is converted to other voltages to better suit the different types of users.

Utilities

Finally, the electricity arrives at the consumers and therefore at the different sectors, for example: residential, industrial.

Typically the electricity value chain is following a linear and highly centralised motion, moving vertically from the large production plants to the individual consumers; on the other hand, data flows are following the energy chain to provide the TSO with the information needed to balance the network together with the data provided by production.

However, this scheme is undergoing a major paradigm shift. The electricity system is increasingly pervaded by distributed generation, i.e. that part of small-scale electricity generation is dispersed throughout the territory and connected directly to the distribution network. This distributed generation is characterised by increasing percentages of renewable sources. The high rate of investment in renewables has brought these technologies within the reach of a much wider public than before, who are increasingly concerned about their energy independence.

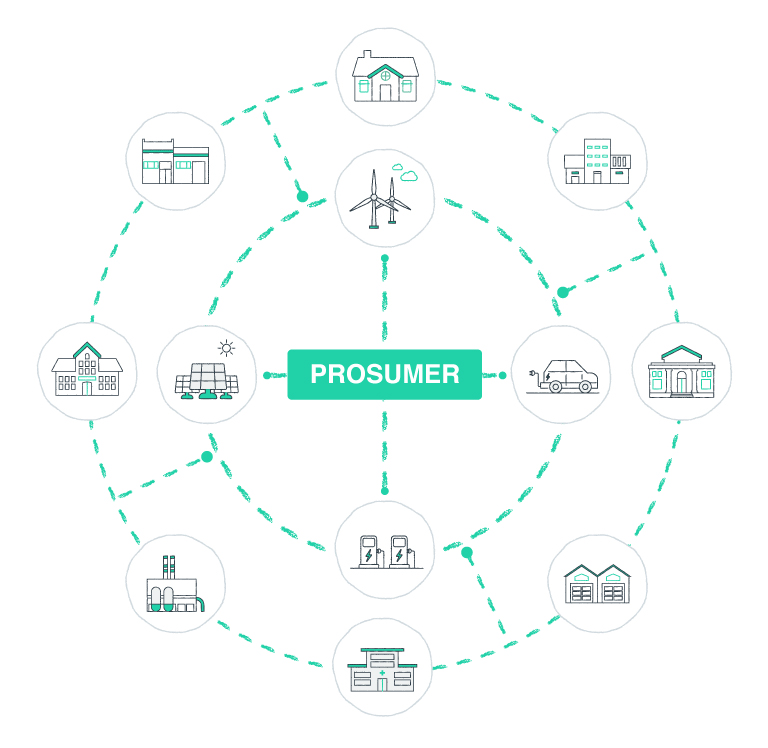

This is how the figure of the “prosumer” was born, a term that combines the two words producer and consumer, able to actively communicate with the energy system within a two-way exchange not only of data but also of energy.

The public push to decarbonise and electrify the energy system has opened up the electricity system to prosumers. The linear model of energy is changing towards a circular model, where the prosumer is at the centre of the system and the grid, large producers, and distributors dialogue horizontally with it.

The deployment of storage systems as a dowry to each prosumer will allow the latter to carve out an important role in balancing the grid, where intelligent management of energy demand will have equal weight to the availability of energy production itself.

Typically the electricity value chain is following a linear and highly centralised motion, moving vertically from the large production plants to the individual consumers; on the other hand, data flows are following the energy chain to provide the TSO with the information needed to balance the network together with the data provided by production.

However, this scheme is undergoing a major paradigm shift. The electricity system is increasingly pervaded by distributed generation, i.e. that part of small-scale electricity generation is dispersed throughout the territory and connected directly to the distribution network. This distributed generation is characterised by increasing percentages of renewable sources. The high rate of investment in renewables has brought these technologies within the reach of a much wider public than before, who are increasingly concerned about their energy independence.

This is how the figure of the “prosumer” was born, a term that combines the two words producer and consumer, able to actively communicate with the energy system within a two-way exchange not only of data but also of energy.

As a result of the increased exchange of energy on the grid between prosumers, it is expected that the electricity grid will become more and more like an energy ”marketplace”, rather than a mere technical transmission and distribution infrastructure.

In the future, the total installed capacity of prosumers is expected to gain in importance. The European Commission, in its package of measures to innovate electricity markets called “Clean Energy for all Europeans”, estimates that by 2050 half of European households will be producing some of their energy.

The electricity system will therefore have to use new technologies such as the Smart Grid and IoT to deal with the additional level of complexity that prosumers will bring to the scheme. Although balancing the grid will become more complex for the TSO, there will be many benefits for the environment, thanks to reduced grid losses and lower climate-altering gas emissions from renewable generation.